Dr. Ryan W. McEwan

Callery pear (Pyrus calleryana) was an extremely popular ornamental tree in the United States that was planted in many neighborhoods. It has since become a highly problematic invasive tree and is presently banned from sale in some states. The story of this transformation is outlined in this article in The Conversation:

Understanding the ecology of Callery pear invasion has been a goal in the McEwan Lab for the past several years. In the lab we are exploring (a) the profile of traits that enable this species to become invasive, (b) the characteristics of ecosystems that make them more (or less) susceptible to invasion, and (c) the effects this species has on ecosystems . We are increasingly studying methods to control Callery pear invasion and restore ecosystems that have been invaded.

Here are some things we have discovered in our research so far:

___________________

Callery pear has an extended leaf duration and is frost resistant

__________________

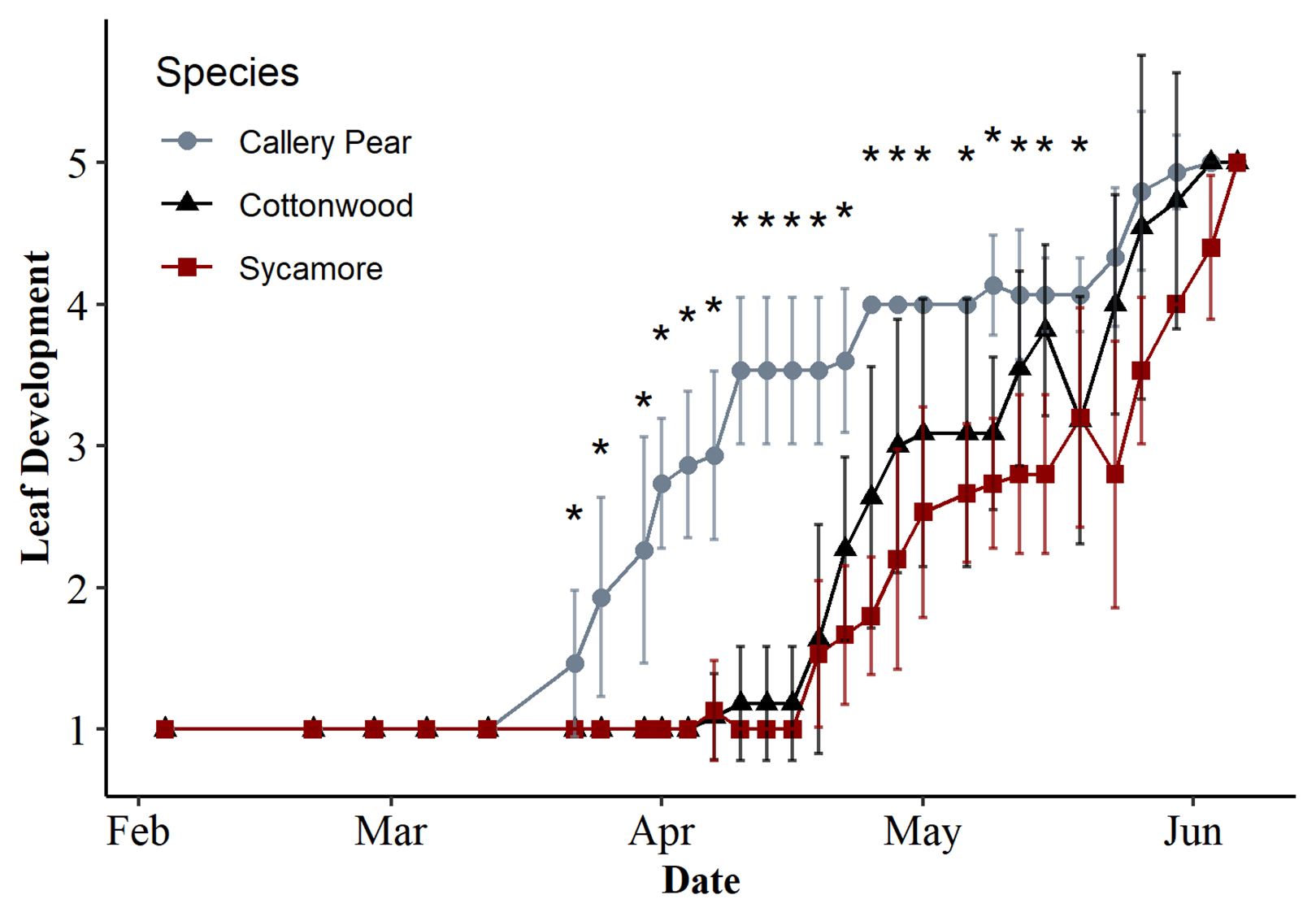

In temperate regions, like Ohio, most woody plants drop their leaves in the fall and go into a semi-dormancy stage in the winter before sprouting leaves again in the spring. The length of time during the year when the leaves are active is important for the plant from the perspective of gaining energy. We noticed that Callery pear seemed to have a longer leaf duration than many native trees and wanted to examine this more closely. In this study, we monitored Callery pear and two co-occurring native trees in grasslands near Dayton, OH. We found that Callery pear had a much earlier leaf out in the spring than either cottonwood (Populus deltoides) or sycamore (Platanus americana).

In the graph above, the grey points with the stars are above the other colored points from mid-March through late May–> This indicates more advanced leaf development for Callery pear than the other plants in the study during this time period. There was a hard frost event during our study and we found that Callery pear suffered virtually no damage while both native species lost nearly all their leaves. We found that Callery pear also held its leaves nearly a month longer in fall. The increased opportunity for growth could be an important component of the invasion biology of Callery pear.

You can read the entire open access paper at this LINK.

Here is the citation for this work:

Maloney, M.E., A. Hay, E.B. Borth and R.W. McEwan. 2022. Leaf phenology and freeze tolerance of the invasive tree Pyrus calleryana (Roseaceae) and potential native competitors. Journal of the Torrey Botanical Society 149: 273-279. Open Access: https://doi.org/10.3159/TORREY-D-22-00008.1

______________________

Callery pear invasion into grasslands is facilitated by adjacent forest

______________________

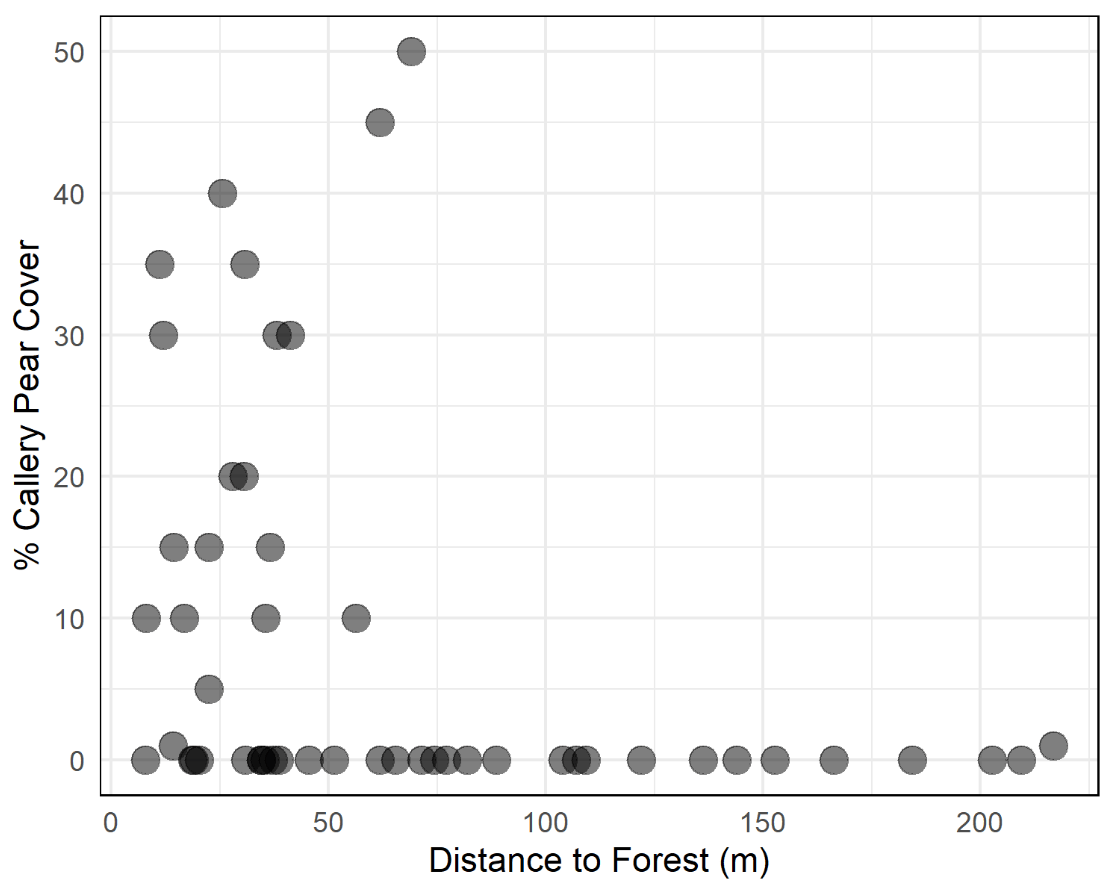

Ecological invasion into grasslands is a process that may be influenced by landscape features. The invasive plant must disperse into the habitat, and for Callery pear that dispersal mechanism is generally though to be through animal dispersal by birds. We were interested in how landscape features might influence the invasion process for Callery Pear. We sampled restored grassland sites with varying levels of invasion of Callery pear and measured the distance from each plot to various landscape features. The most important factor that we discovered in dictating initial invasion of Callery pear was distant to a forest edge.

In the graph above, each of the dots is a plot, how high the points are indicates the level of Callery pear cover in the plot and how far to the right each point is indicates how far away that plot was from a forest edge. We saw that after approximately 75 meters from the forest edge there were not plots containing Callery pear. This indicates an “edge – to – interior” pattern of the invasion process. This may be related to bird roosting sites in the forest edge. Hypothetically, the birds eat the Callery pear fruits then land at the edge of the field in trees and deposit the fruits while roosting. A lot more work is needed to verify this pattern and assess the mechanism(s) responsible. If you have observations of animals eating Callery pear fruits, please share them with us at this link.

You can read the dissertation chapter from which this article was created here (Chapter 2): LINK

The citation for this work is here:

Woods, M.J., G. Dietsch and R.W. McEwan. 2022. Callery pear invasion in prairie restorations is predicted by proximity to forest edge, not species richness. Biological Invasions 24: 3555–3564. LINK.

______________________

Callery pear suppresses seed germination of some native grassland species

____________________

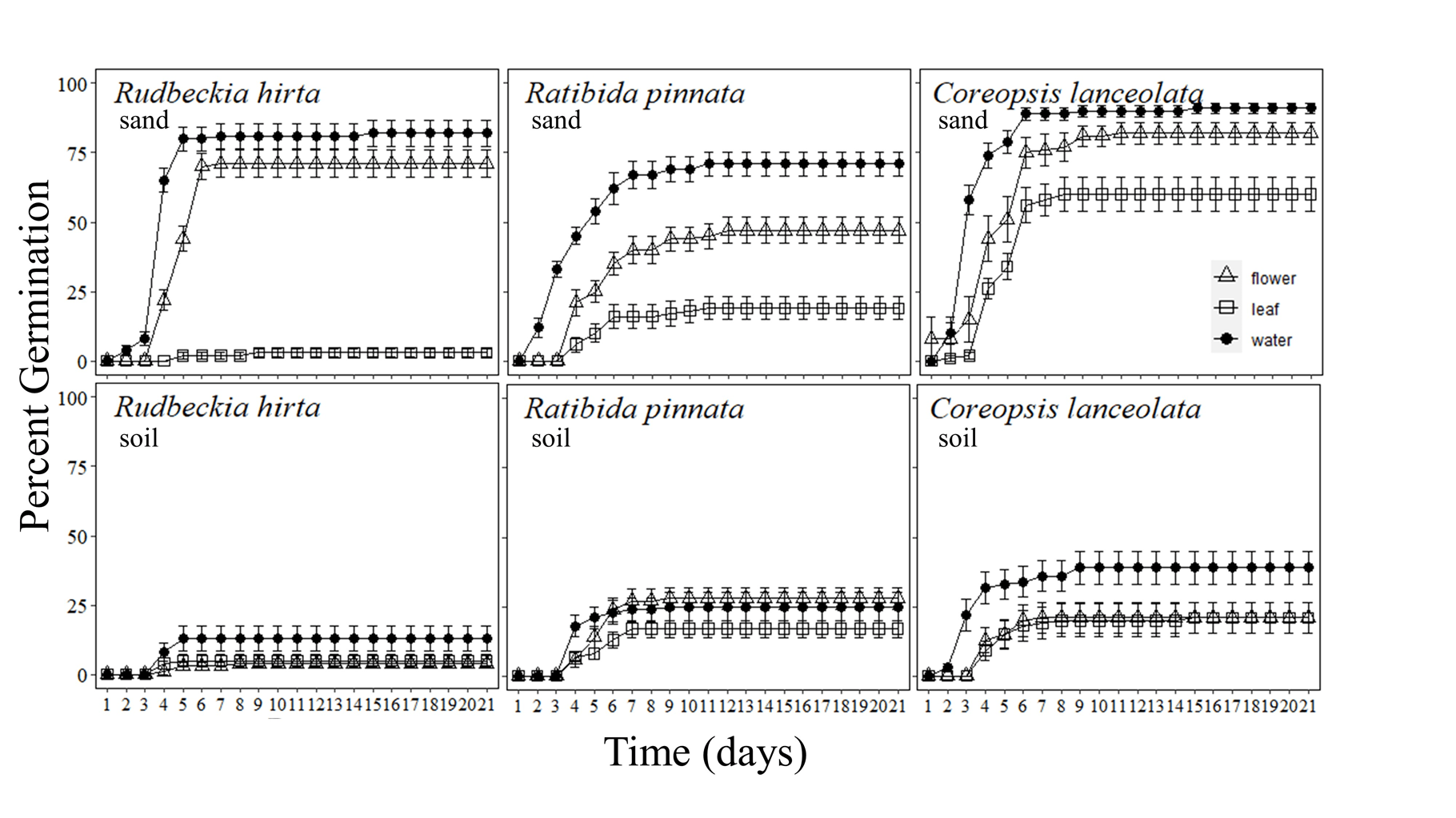

In central Ohio were our lab is located, we have noted many dense stands of Callery pear in open fields. We were curious as to how those trees established dominance so quickly. One way many invasive species, including Amur honeysuckle, are able to establish dominance is through suppression of potential competitors through chemical inhibition of seed germination. To test this idea, we conducted a series of laboratory assays in which we applied leaf exudates to native grass and forb seeds and monitored germination. We found strong evidence of allelopathic inhibition of native seeds when exposed to P. calleryana exudates.

In the graph above, look for the black circles and compare those to the open squares- where you see the black circles above the squares that is a point in time when the germination of the native plant is being inhibited by the exudates from leaves of Callery pear. We did this kind of experiment with grasses and with forbs and saw compelling results that suggest that Callery pear may be limiting competition by suppressing germination of potential competitors. Further work is need to verify this effect in field conditions and isolate the responsible compounds.

You can read the entire open access paper at this Link.

Here is the citation for this work:

Woods, M.J., D. Schaeffer, J.T Bauer and R.W. McEwan. 2023. Pyrus calleryana exudates reduce germination of native grassland species, suggesting the potential for allelopathic effects during ecological invasion. PeerJ 11:e15189. Open Access: https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.15189

______________________

Callery pear invasion influences soil biology

______________________

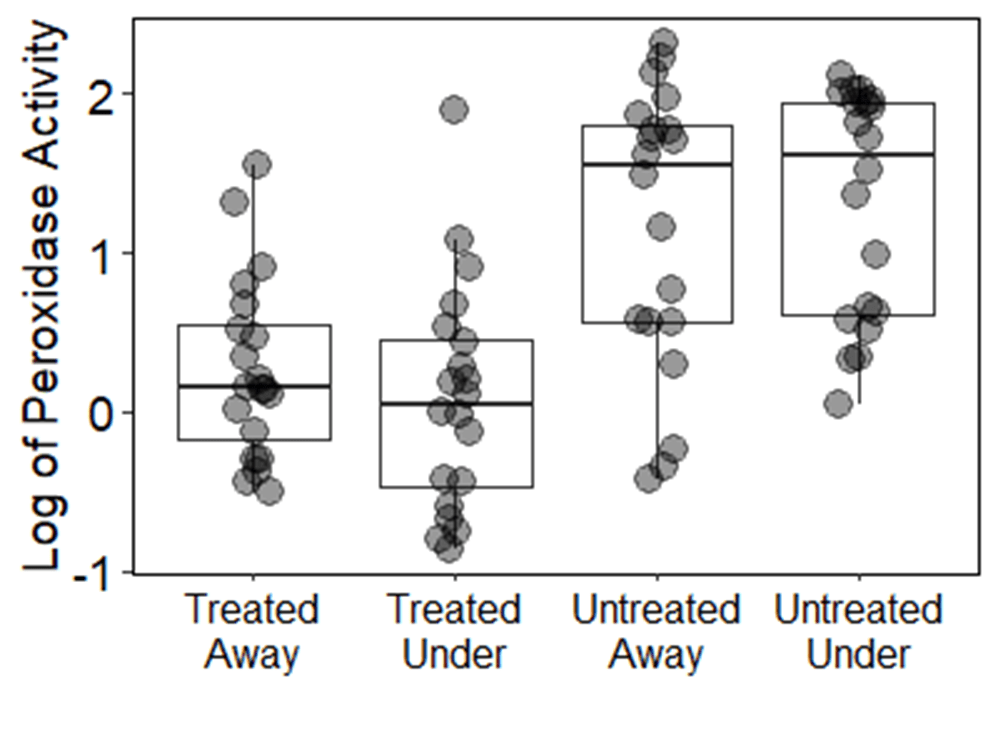

Invasive plants have strong potential to alter ecosystem function in areas where they invade. These effects can include altering soil nutrients and microbial activity. We were interested in testing for potential effects of Callery pear on soil nutrients and microbial activity. We used soil enzyme activity as a way to measure the soil microbial community. We analyzed soil under and away from Callery pear stems in two conditions: (a) “treated” stems, which had been previously cut by land managers as part of control efforts and (b) “untreated” stems that had never been cut. We found strong evidence that cutting the stems activates biological changes in the root system that alters soil chemistry. We analyzed soil enzyme activity as a way to assess overall soil microbial ecology and found significant differences among treated and untreated stems. Future studies aimed at understanding how invasion & control activities alter soil ecology are needed.

You can read the dissertation chapter from which this article was created here (Chapter 3): LINK

Here is the citation for this work:

Woods, M.J., G.K. Attea and R.W. McEwan. 2021. Resprouting of the woody plant Pyrus calleryana influences soil ecology during invasion of grasslands in the American Midwest. Applied Soil Ecology 166: 103989. LINK.

____________________

Callery pear sprouts aggressively and can survive both fire and ice!

____________________

In a series of field experiments we clipped Callery pear stems in the field then applied treatments to control sprouting.

We applied fire to small plots containing Callery pear stumps:

#########

We also applied liquid nitrogen to Callery pear stumps to freeze the stumps:

We applied these treatments to both stems that had been repeatedly mown before the start of the experiment (we called this “trees-sprouting”), and also to trees that had never been cut (we called this “trees-intact”).

Above you can see a graph from the paper, from the trees-sprouting part of the study. The height of the line in the middle of the boxes represent the number of sprouts that came back after the Callery pears where cut and then treated with one of the treatments. “Cut” are stems that were only cut and not treated. “Fire” were cut first and then burned with prescribed fire. “Freeze” were cut first and then frozen with liquid nitrogen. “Herb” were cut and sprayed with herbicide. “Neg” is a “negative control”- those stems were not cut at all. The point of the graph is that only herbicide actually reduced the number of stems (box below the dotted line). The number of sprouts actually increased in all the other treatments. What is really interesting in this graph is that the number of sprouts from Callery pear stumps that were burned (red box) is actually increased relative to the negative control (white box), suggesting that fire increased the number of sprouts! Fire is a common practice in maintaining grasslands in the American Midwest, so this result is very concerning.

You can read the entire open access paper at this LINK.

Here is the citation for this work:

Maloney, M.E., E.B. Borth, G. Dietch, M.C. Lloyd and R.W. McEwan. 2023. A trial of fire and ice: assessment of control techniques for Pyrus calleryana stems during grassland restoration in southwestern Ohio, USA. Ecological Restoration 41: 25-33. Open Access: https://muse.jhu.edu/pub/19/article/883911

___________________

A way out of the pear predicament?

____________________

Callery pear has a profile of advantageous traits including early phenology, allelopathy, and aggressive sprout response that make it an extremely effective invader. This species is influencing grassland ecosystems in the Midwest and “natural” control measures are ineffective. Herbicides are required to manage this plant; however, once you apply herbicide, the site is likely to be re-invaded. Ongoing work in the lab focuses on how to advance native species success in the presence of this invasive tree – we are currently running experiments to see if we can “hold the niche” against re-invasion.

____________________

McEwan Lab Publications focused on the biology of Callery Pear invasion:

____________________

Woods, M.J., D. Schaeffer, J.T Bauer and R.W. McEwan. 2023. Pyrus calleryana exudates reduce germination of native grassland species, suggesting the potential for allelopathic effects during ecological invasion. PeerJ 11:e15189. Open Access: https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.15189

Maloney, M.E., E.B. Borth, G. Dietch, M.C. Lloyd and R.W. McEwan. 2023. A trial of fire and ice: assessment of control techniques for Pyrus calleryana stems during grassland restoration in southwestern Ohio, USA. Ecological Restoration 41: 25-33. Open Access: https://muse.jhu.edu/pub/19/article/883911

Maloney, M.E., A. Hay, E.B. Borth and R.W. McEwan. 2022. Leaf phenology and freeze tolerance of the invasive tree Pyrus calleryana (Roseaceae) and potential native competitors. Journal of the Torrey Botanical Society 149: 273-279. Open Access: https://doi.org/10.3159/TORREY-D-22-00008.1

Woods, M.J., G. Dietsch and R.W. McEwan. 2022. Callery pear invasion in prairie restorations is predicted by proximity to forest edge, not species richness. Biological Invasions 24: 3555–3564. LINK.

Woods, M.J., G.K. Attea and R.W. McEwan. 2021. Resprouting of the woody plant Pyrus calleryana influences soil ecology during invasion of grasslands in the American Midwest. Applied Soil Ecology 166: 103989. LINK.

McEwan Lab Callery Pear Data sets: